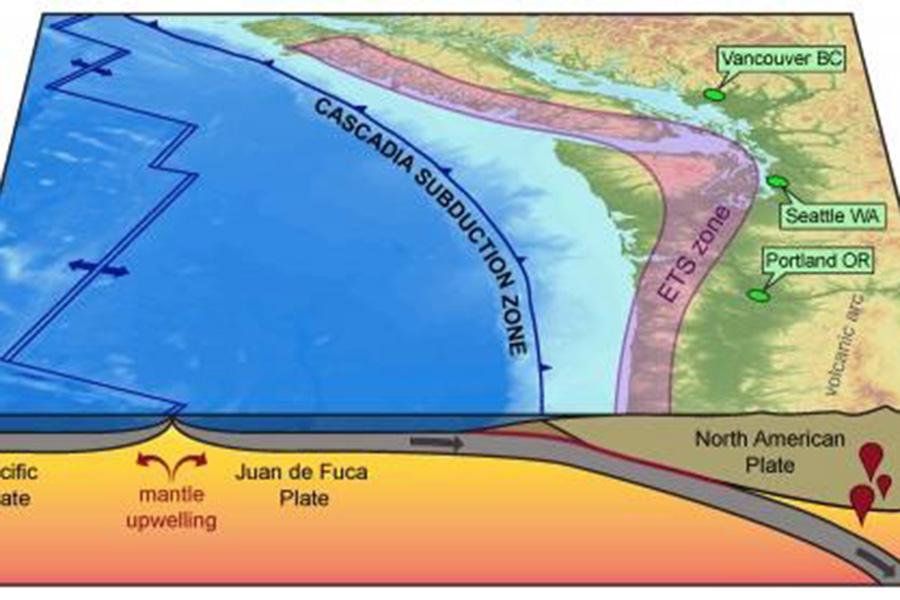

Megathrust earthquakes and subsequent tsunamis that originate in subduction zones like Cascadia — Vancouver Island, Canada, to northern California — are some of the most severe natural disasters in the world. Now a team of geoscientists thinks the key to understanding some of these destructive events may lie in the deep, gradual slow-slip behaviors beneath the subduction zones. This information might help in planning for future earthquakes in the area.

The asteroid impact 66 million years ago that ushered in a mass extinction and ended the dinosaurs also killed off many of the plants that they relied on for food. Fossil leaf assemblages from Patagonia, Argentina, suggest that vegetation in South America suffered great losses but rebounded quickly, according to an international team of researchers.

Tucked into the rolling hills of Stone Valley, Cole Farm seems like a typical central Pennsylvania farm. A gravel driveway slopes down to a steel and wood-plank bridge that spans Shaver’s Creek. The path continues relatively flat, past a murky green retention pond and two barns, to a log farmhouse nestled at the base of a hill. A spring trickles through the wooded swale west of the house. Sloping fields are flush with alfalfa, corn, hay grass, and wheat.

Geoscientists have long known that some parts of the continents formed in the Earth’s deep past, but the speed in which land rose above global seas — and the exact shapes that land masses formed — have so far eluded experts.

While the seas were still churning from the impact and the seawater temperatures were high due to the hydrothermal activity, life was reestablishing itself inside the crater.

Katherine Freeman, Evan Pugh University Professor of Geosciences at Penn State, has been awarded the 2020 Nemmers Prize in Earth Sciences. The prize is awarded by Northwestern University and recognizes achievement and work of lasting significance in the field of Earth sciences.

Freeman was selected “for her pioneering and continued contributions to development of the field of compound-specific stable isotope geochemistry and its application to fundamental problems in Earth science."

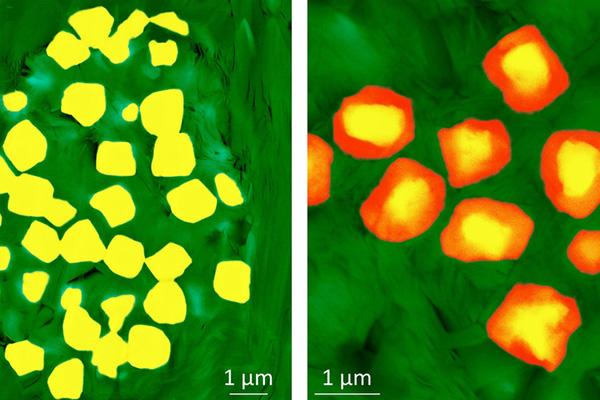

Pyrite, or fool’s gold, is a common mineral that reacts quickly with oxygen when exposed to water or air, such as during mining operations, and can lead to acid mine drainage. Little is known, however, about the oxidation of pyrite in unmined rock deep underground.

A new, multi-scale approach to studying pyrite oxidation deep underground suggests that fracturing and erosion at the surface set the pace of oxidation, which, when it occurs slowly, avoids runaway acidity and instead leaves behind iron oxide “fossils.”

When the Paleocene ended and the Eocene began nearly 56 million years ago, Earth’s atmospheric carbon dioxide levels ranged between 1,400 and 4,000 parts per million (ppm). These carbon dioxide levels gave rise to sauna-like conditions across the planet, which scientists can now measure using tiny minerals called siderites.

With rising temperatures in the Arctic, communities in Alaska’s North Slope Borough are seeing the ground beneath their feet melt away.

“Climate change is thawing the frozen soil,” said Ming Xiao, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Penn State. “The borough spends $100 million a year just for repairs to roads, buildings and pipelines. To build resilient infrastructure in the changing Arctic, we need to understand how the soil behaves as it softens.”

Rocks from the Rio Grande continental rift have provided a rare snapshot of active geology deep inside Earth’s crust, revealing new evidence for how continents remain stable over billions of years, according to a team of scientists.

“We tend to study rocks that are millions to billions of years old, but in this case we can show what’s happening in the deep crust, nearly 19 miles below the surface of the Earth, in what geologically speaking is the modern day,” said Jacob Cipar, a graduate student in geosciences at Penn State. “And we have linked what’s preserved in these rocks with tectonic processes happening today that may represent an important step in the development of stable continents.”